Near the airport in Aspen — the Colorado city known both for its snow-covered slopes and glitzy affluence — is a restaurant that offers diners a true reprieve from the sometimes sterile-feeling winter conditions outside. At Mawa’s Kitchen, Chef Mawa McQueen serves bold, Afro-Fusion food like Berbere Spiced Chicken Yassa and Colorado Lamb Tagine in a bright, welcoming dining room.

Both McQueen and her restaurant, which is the only Black-owned restaurant in the city, have earned numerous accolades in recent years, including a Michelin recommendation, a James Beard nomination and being dubbed the Colorado Governor’s Minority Business of the Year in both 2020 and 2022.

Related

This unique supper club has a deep purpose: Honoring the work of enslaved chefs throughout history

Her first cookbook, “Mawa’s Way,” which is a showcase of her career and approach to food and restaurants thus far, further establishes her as a trailblazer in an industry that often skews younger, white and male. "I want readers to learn about my beginnings with Mawa's Kitchen, the grit and determination it took to keep this dream going and how I've evolved since I've started,” McQueen told Salon Food.

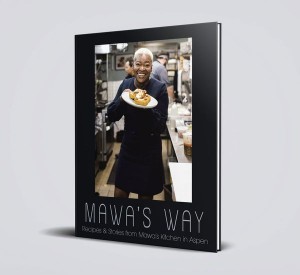

Cover of Mawa's Way, Chef Mawa McQueen's new cookbook (Photo courtesy of McQueen Hospitality)

Cover of Mawa's Way, Chef Mawa McQueen's new cookbook (Photo courtesy of McQueen Hospitality)

McQueen grew up in Africa’s Ivory Coast and was the oldest of 11 children. She learned some of the culinary basics while caring for them, which launched a passion for cooking that she carried through time living in France where she learned cooking styles from Tunisian, Algerian and Moroccan friends. McQueen says that the blend of her African roots and Parisian culinary knowledge and experience are “such a festival of color and taste.” Over time, though, McQueen has melded these varying influences and styles into a genre that is entirely hers unto itself.

“I am always refining and reinventing recipes and adding pieces of my cultures and experiences in them through ingredients, cooking techniques, plating, [etcetera],” McQueen said. “Usually when I create an African dish it is not a thing you are going to find in Africa, it’s my own touch because I am in Aspen, Colorado, and sourcing the right ingredients is hard."

So, it must be asked — why Aspen? It’s actually a simple story, per McQueen.

“The first time I saw Aspen it was on an episode of ‘The Young and the Restless,’” she said. “It looked like a Hallmark Channel town, just beautiful with the snow and the scenery and the whole romance of it. All it took was that one look and I knew I needed to be there."

McQueen now has three restaurants in the city. There’s Mawita, which serves Afro-Latin cuisine, The Crepe Shack — a “love letter from France to American,” which McQueen says is “a childhood dream realized” — and Mawa’s Kitchen. When McQueen first opened Mawa’s Kitchen in 2012, it initially focused entirely on healthy eating since that’s what her customers wanted, but she’s since transitioned to healthy food in an Afro-fusion style “with hints of French and American classics because I was tired of doing what everybody else was doing.”

Mawa's Kitchen interior (Photo courtesy of Darren Bridges)

Mawa's Kitchen interior (Photo courtesy of Darren Bridges)

She continued: “I wanted to bring myself and my culture into the dishes … [and not] play it safe.”

We need your help to stay independent

Subscribe today to support Salon's progressive journalism

That’s exactly what McQueen brings to her cookbook, “Mawa’s Way,” as well. It is packed with recipes that point to her own heritage, like her West African Gumbo with Fou Fou, as well as dishes that reflect her various influences from Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, like the tagine, tabbouleh and batata harra.

If you’re unfamiliar with fou fou, it is, as McQueen puts it, “essentially the starchy vessel” with which to eat many traditional West African stews and sauces. “Sometimes it’s made from pounded yam, but in the Ivory Coast, where I am from, we do it with plantain and yucca,” she said.

The produce is steamed or boiled before being pounded and made into a type of stretchy dough (“a real arm workout,” McQueen jokes) that becomes essentially an edible utensil since “in West Africa, you use your hands to eat everything.” She recommends making a little depression in the middle of the dough, and then putting the sauce or stew into the fou fou.

Want more great food writing and recipes? Subscribe to Salon Food's newsletter, The Bite.

In terms of differentiating between West African gumbo and gumbo from the Southern United States, McQueen says there are a few distinctions. West African gumbo tends to be made with way, way more okra and, instead of relying on a roux or mirepoix to impart flavor, it contains dried fish powder, shrimp powder and “heavy-duty spices.”

However, the biggest difference comes down to texture and “sliminess.”

“If it’s not slimy, you f**ked it up and people from West Africa won’t eat it,” McQueen said.

At this point in her career, McQueen oversees a lauded, awarded restaurant and has also been featured in the 2019 book "Toque in Black: 'Savor' The Extraordinary Diversity of Black Chefs," featuring over 100 of the most talented chefs across the country.

Given all her recent success, it would make sense if McQueen wanted to kick back for a bit to enjoy the winter wonderland where she lives, but she doesn’t see herself slowing down anytime soon. So what's next?

Chef Mawa McQueen (Photo courtesy of McQueen Hospitality)

Chef Mawa McQueen (Photo courtesy of McQueen Hospitality)

"I am so honored with what I have and what I have received, but they don’t mean squat until I am at the very top,” she said. “My accolades are driving me to want to accomplish more, to get to the top and win the awards, not simply be nominated. Now I want to get a Michelin star and I want to win a James Beard Foundation Award."

Also, McQueen says that “Mawa’s Way” is only a warm up of what’s to come in terms of her writing career. She’d love to work on a “full African recipe cookbook,” too.

Spread of tapas at Mawa's Kitchen in Aspen, CO

Spread of tapas at Mawa's Kitchen in Aspen, CO